1979, Torinoko Japanese paper, charcoal, felt pen, wood, bamboo, twig, watercolor, wire on vinyl, 132×93×23cm

1987–1989, Bamboo, wood, paper, leather, lead, 92×450×460cm

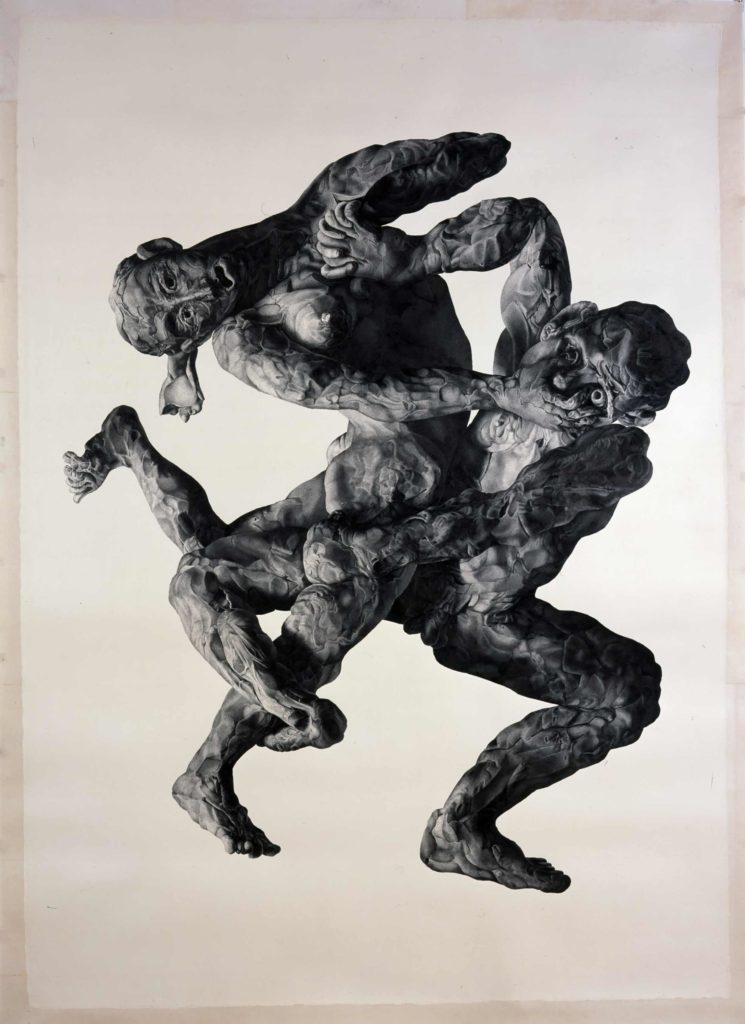

1986, Black ink on Torinoko Japanese paper, 213×152cm

2007, Black ink on Torinoko Japanease paper, 213×153cm

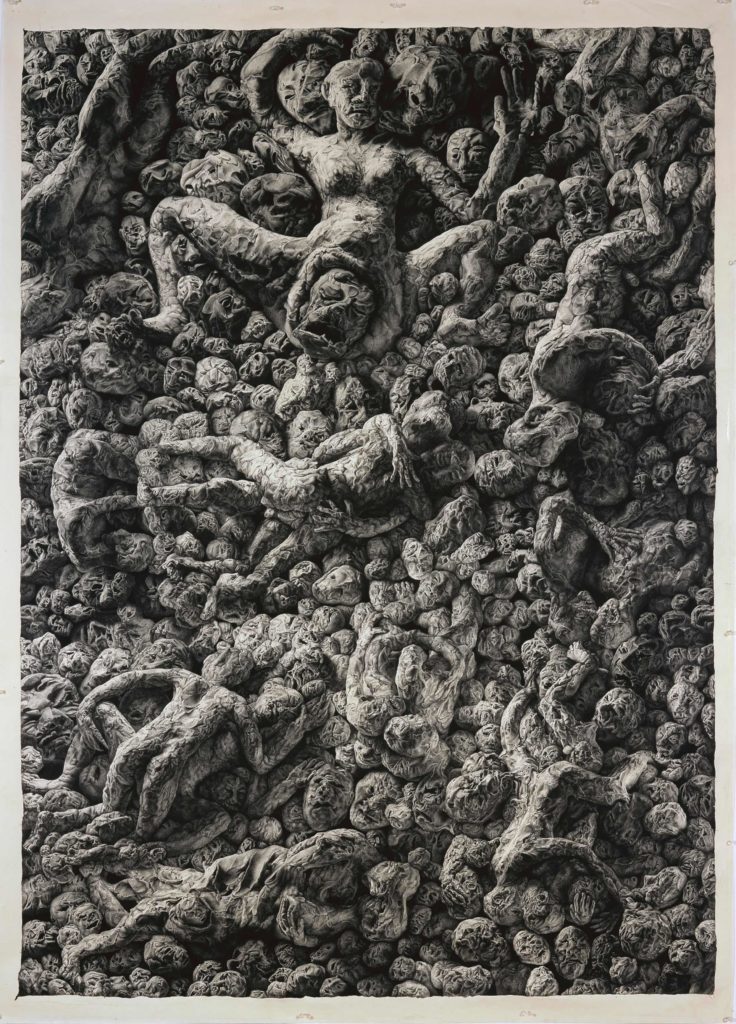

2012–2013, Black ink on Torinoko Japanease paper, 220×161cm

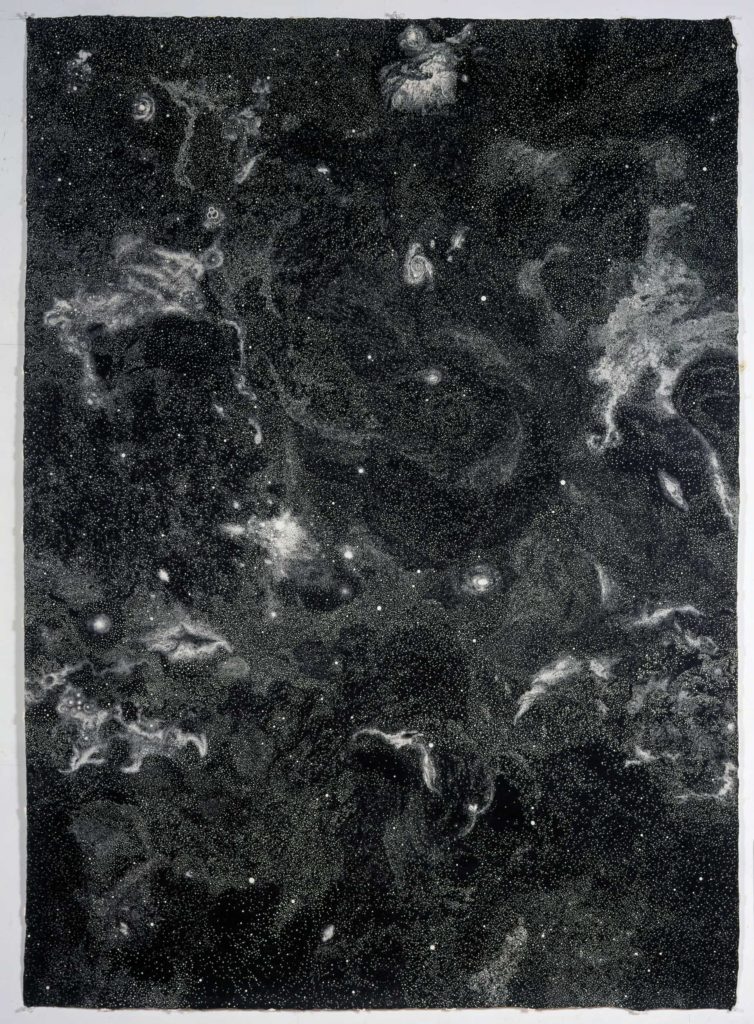

2000, Black ink on Torinoko Japanese paper, 213.5×153cm

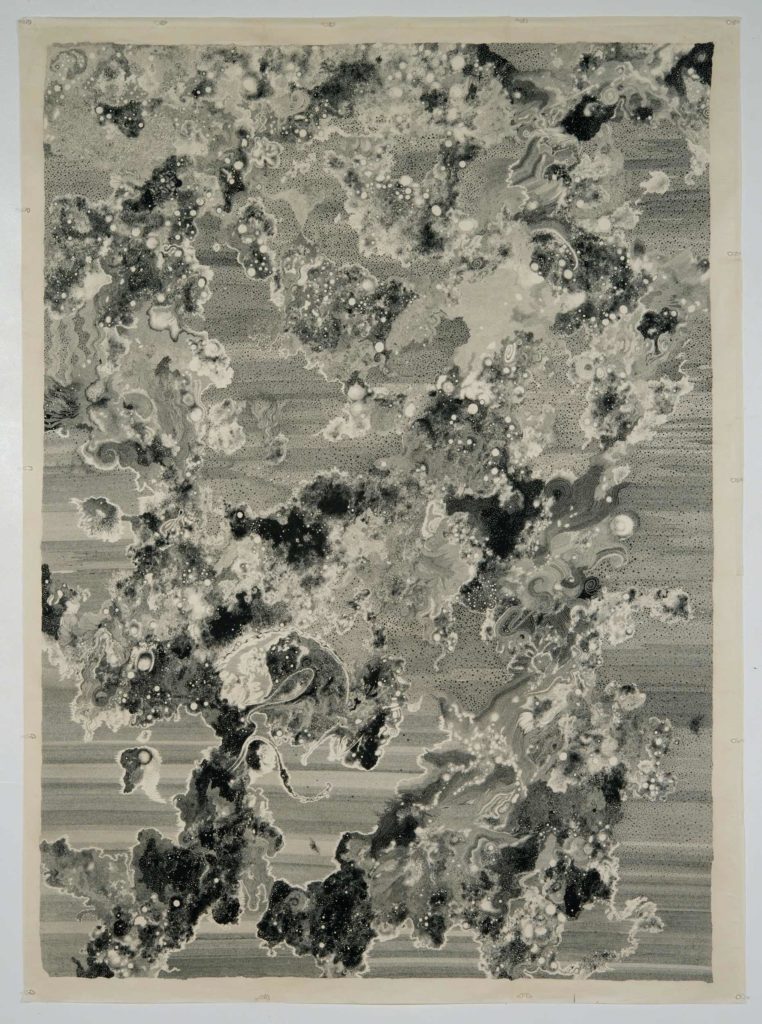

2018, Black ink on Torinoko Japanese paper, 212×152cm

2006-2017, Black ink on Torinoko Japanese paper, 212×435.9cm

Black ink on Torinoko Japanese paper

“My wish is to make possible the one and only me through my works.”

(Yoshio Kitayama, The National Museum of Art, Osaka, Monthly Bulletin 134)

Children’s Drawings

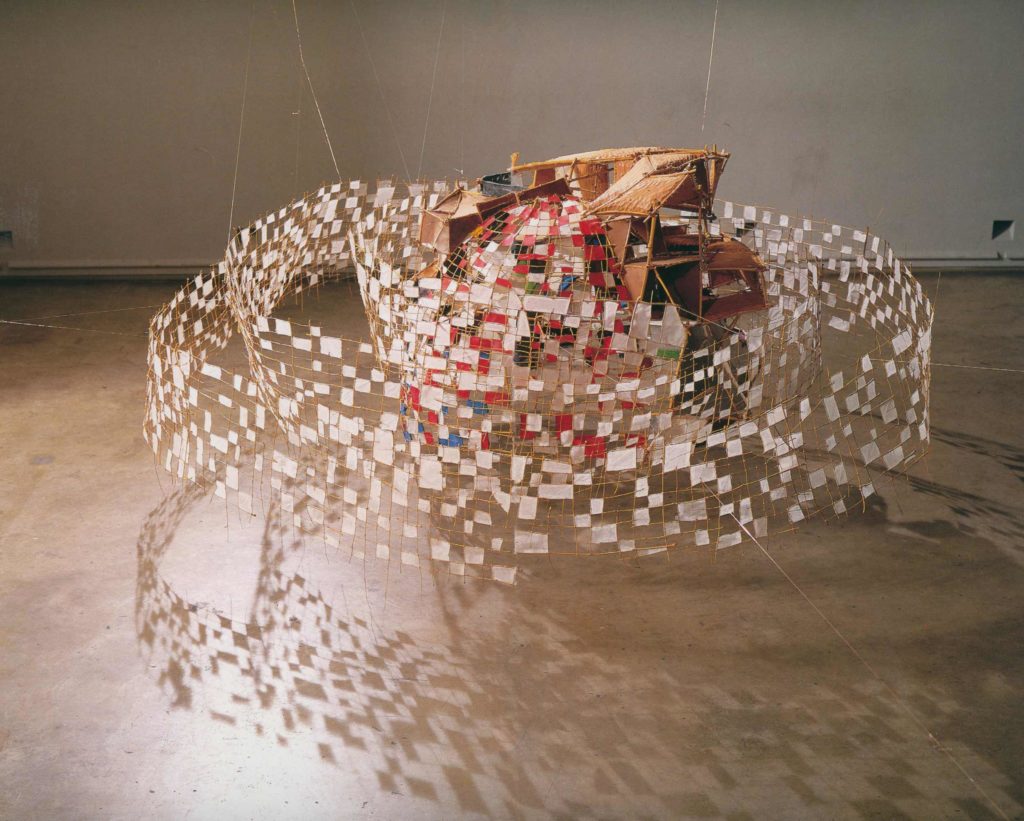

Kitayama began his career as a self-taught painter while working at a dying factory. He gradually began creating large-scale three-dimensional works using simple materials such as bamboo and Japanese paper. The inspiration for these later works stemmed from drawings produced in the wholehearted engrossment of childhood. He had an epiphany as an adult when he looked at children’s drawings.

“They were so alive. They depicted a world that was free, unencumbered by anything. There was a strong connection between the person and the drawing. My own works until that moment seemed dead. I tried to draw lines, but they were contemptible; they were lines that were conscious of the gaze of others. I realized that my lines would never achieve that child-like quality and gave up painting” (From Kitayama’s writings). Upon this realization, he began to create three-dimensional works of bamboo, wood, and Japanese paper in 1979. He says that he endeavors to retain the free and lively qualities of the materials through his creative process, akin to a child’s approach to drawing. Kitayama does not make preliminary sketches for his three-dimensional works; he allows the materials to guide him as he shapes them. Eventually, through the 1990s, Kitayama gained acclaim for large-scale three-dimensional works constructed with these simple materials.

However, Kitayama returned to painting in 1982. At that time, Kitayama had no other choice but to reject his past paintings. As he searched for his way of painting for three years, he came to feel that the expression of painting in the art world was folding into itself and had begun to lose contact with society, forfeiting any subject matter.

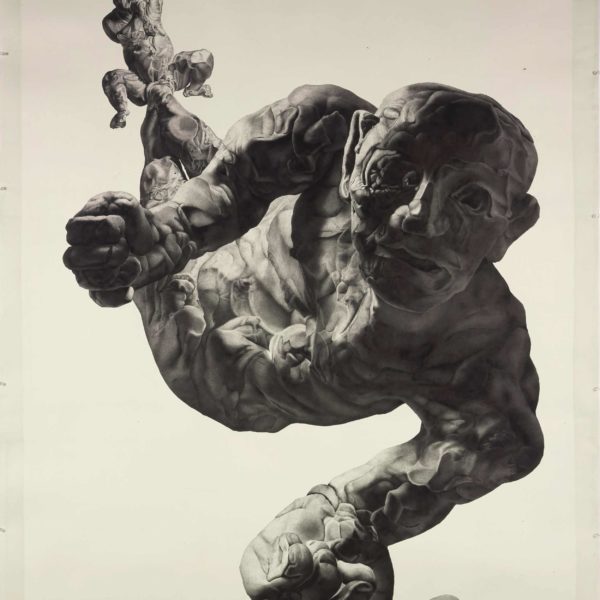

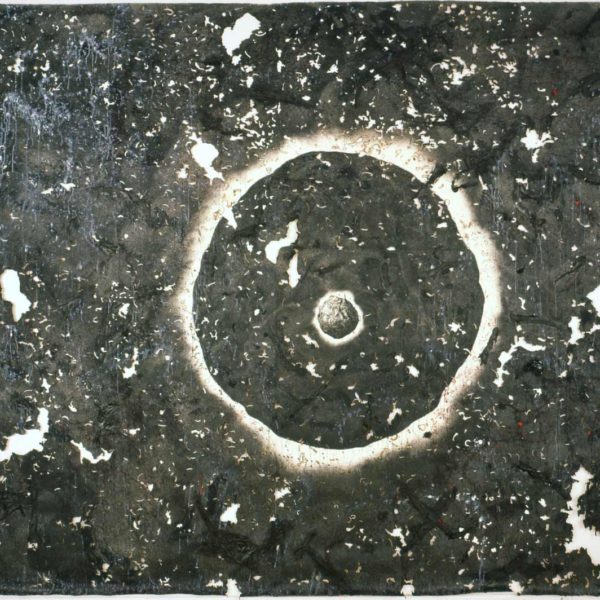

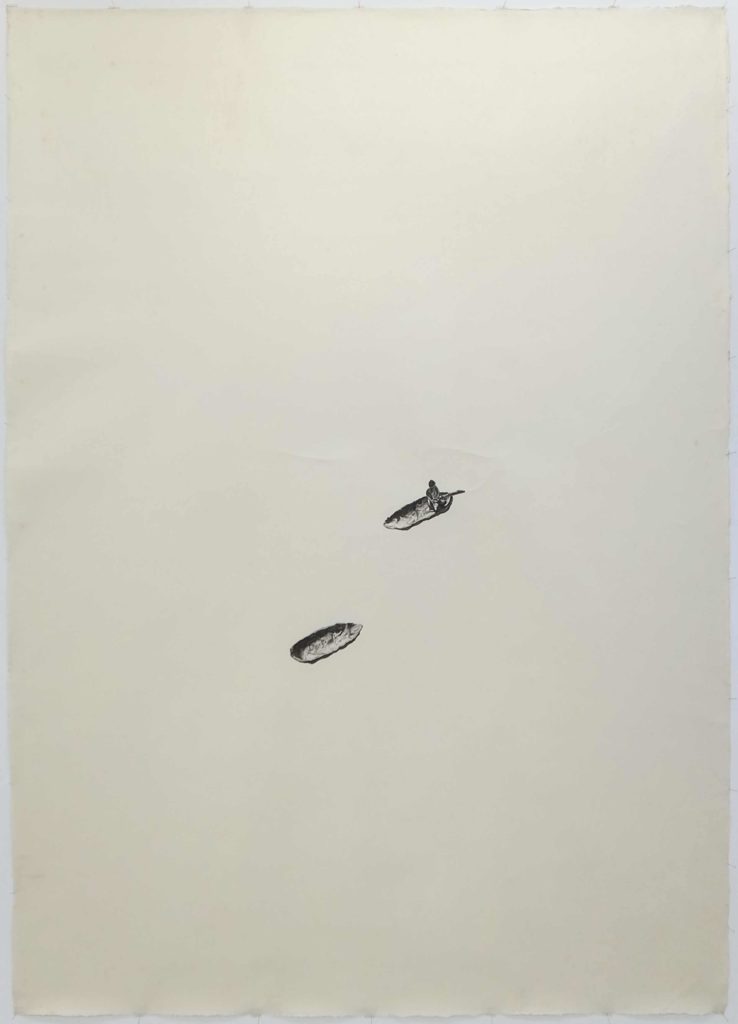

Icon and Universe

Kitayama has continued to work on these two series since he resumed painting. In Icon, he creates a clay human sculpture, which he recreates on paper in ink. After the human sculpture is drawn, the perpetual cycle continues as the clay is reworked into a completely new human figure and subsequently dropped into the pictorial space. These human figures undergo an iconization incorporating themes such as life and death, history and war. The backgrounds of these paintings are complete emptiness, blank white paper. On the other hand, in Universe, the ‘cosmos’ is depicted using an all-over approach, employing a kind of automatic and illustrative style. In both series, the drawings are meticulously created with a Rotrig pen, a precision tool designed for uniform lines. In these works, it is evident that Kitayama has rejected the one-point perspective and spatial composition that rely on the illusion of depth of Western traditions. Inspired by the multi-perspective of Eastern landscape painting, he sets the direction for his artistic development towards a more conceptual composition of space.

“The universe is the birthplace of humankind. It is also the earth and cosmos where we die and return to. Humankind lives in the universe and it is on the planet of earth that we conduct the affairs of our lives. I use clay, soil, to sculpt the affairs of humankind that make up history and the subject of my paintings is the history of birth until death within society” (From Kitayama’s writings).

At the heart of his expression lies his childhood experience confronting the challenges of battling illness.

Considering the figure-ground relationship in art, in the compositional elements of Kitayama’s paintings, the Icon series deals with the figure, the focal point, while the Universe series deals with the ground, the background. The two elements in the composition of paintings have been depicted separately in two different series. For many years, the two never overlapped; the background of the Icon series remained blank, but when he completed The Dead Make History, which he worked on for ten years, countless lifeless bodies filled not only the background but the entirety of the pictorial plane as the figure and ground merged. Meanwhile, the Universe series, which initially depicted figurative planetary formations, gradually achieved another level of abstraction in 2017 in his JIKEN (“Incident”) series.

JIKEN (“Incident”)

In JIKEN (“Incident”), Kitayama dedicated over ten years to the meticulous process of drawing countless circles, each few millimeters in diameter, spanning from one end to the other on a Japanese paper measuring approximately 2×4 meters. When he completed the work, every inch of the paper was filled with minuscule circles, collectively resembling stratigraphic formations. They are one of the crowning achievements of Kitayama’s career. Kitayama himself refers to these works not as abstract but as figurative paintings. This is because each circle is a concrete atom, molecule, or perhaps a cell of our bodies. Yet, in each of these circles, there exists a universe. They come together to constitute our bodies and this world. The microcosm is the macrocosm, and vice versa. All circles are nothingness, but simultaneously, they are universes, and all life is connected. One’s life is born at the end of the endless river of the chain of life. Such are the words of Kitayama.

Kitayama’s studio stands on a cliff in the mountains of Kameoka in Kyoto Prefecture, far removed from human habitation. There, he solemnly draws a vast narrative on Japanese paper with a Rotrig pen, keeping his sights set on his Universe and the history of humankind. His studio is surrounded by a handsome stone wall that Kitayama built himself. Kitayama piles stone in front of his studio, little by little, every day. After several decades, a magnificent stone wall materialized. The artwork unfolds with each daily stroke, much like the steadily accumulating stone wall. The harmony of these rhythmic processes resembles the birth of countless lives, which shape the bedrock of evolution. Each stone and each circular stroke of ink that Kitayama forms a vast milky way in the midst of which our fleeting existence is suspended and disappears. Kitayama continues to depict this sense of impermanence and the chain of life.

(Original text by K.I., Translated by Jin Nakazato)