1962, Vintage gelatin silver print, 67.8×91cm

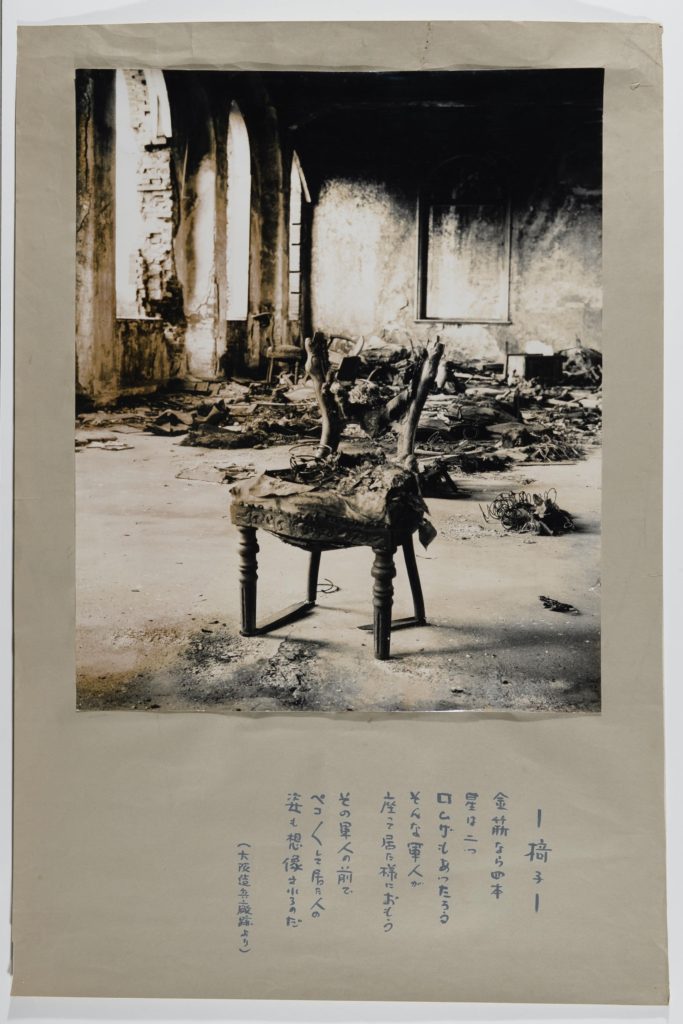

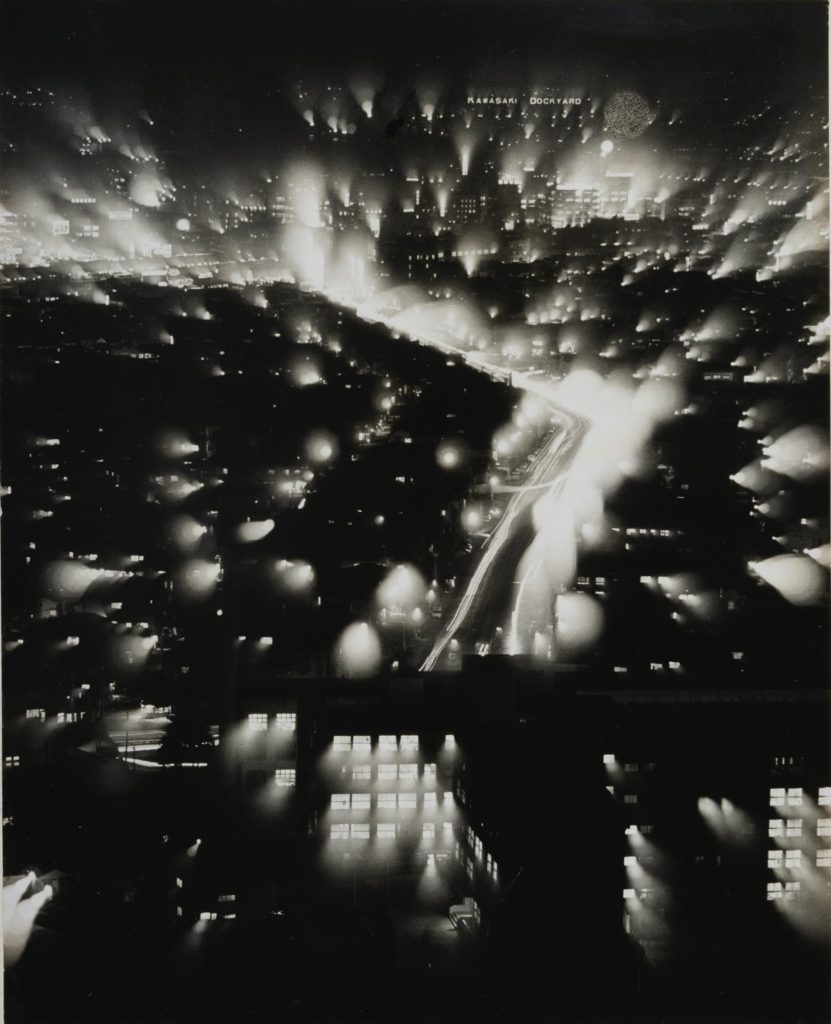

1958, Vintage gelatin silver print mounted on board, titled and text on the mount, 54.4×44.8cm

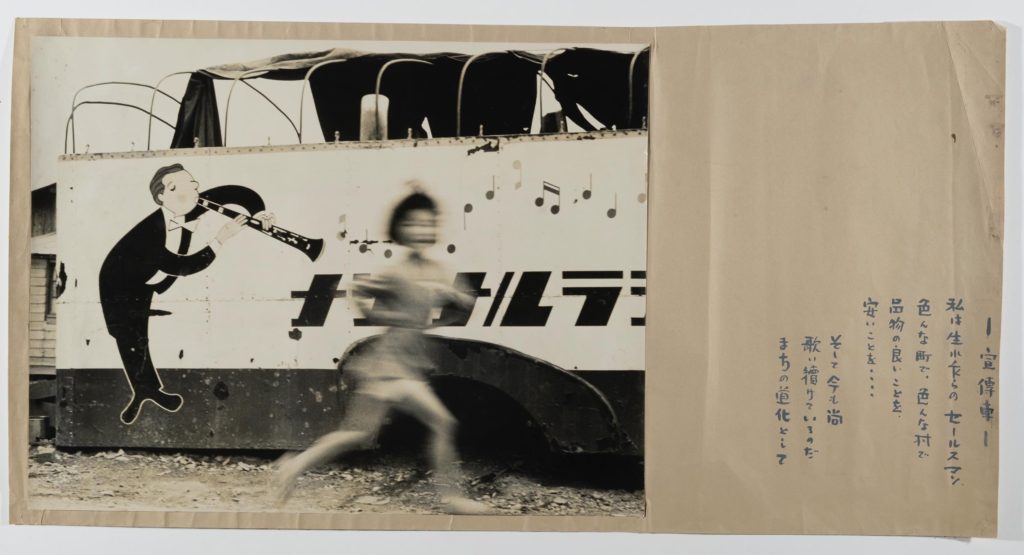

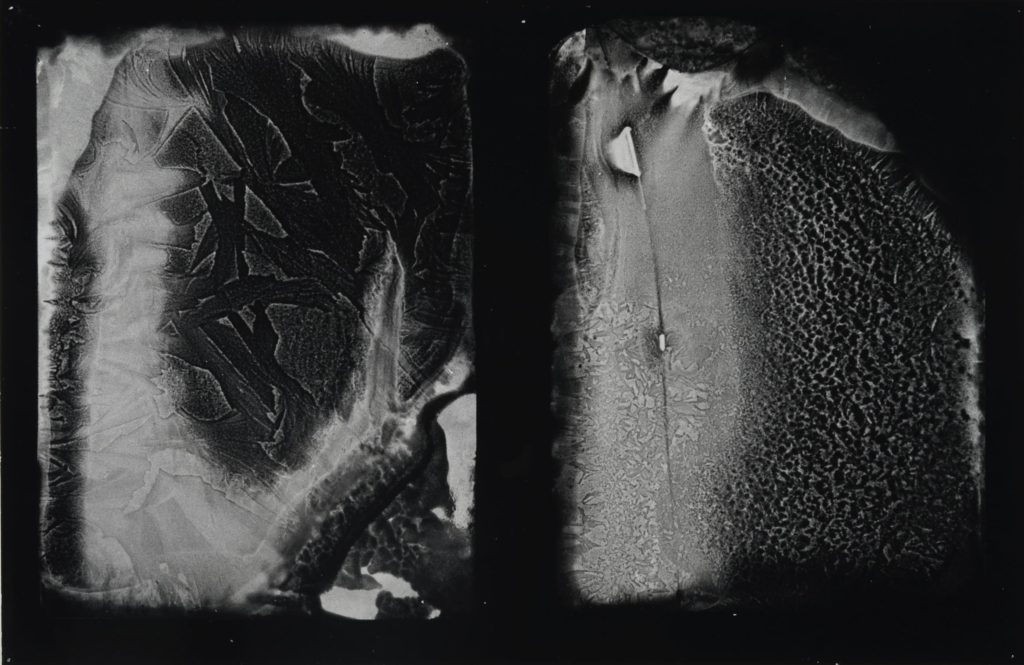

1959, Vintage gelatin silver print mounted on board, titled and text on the mount, 42.1×55cm

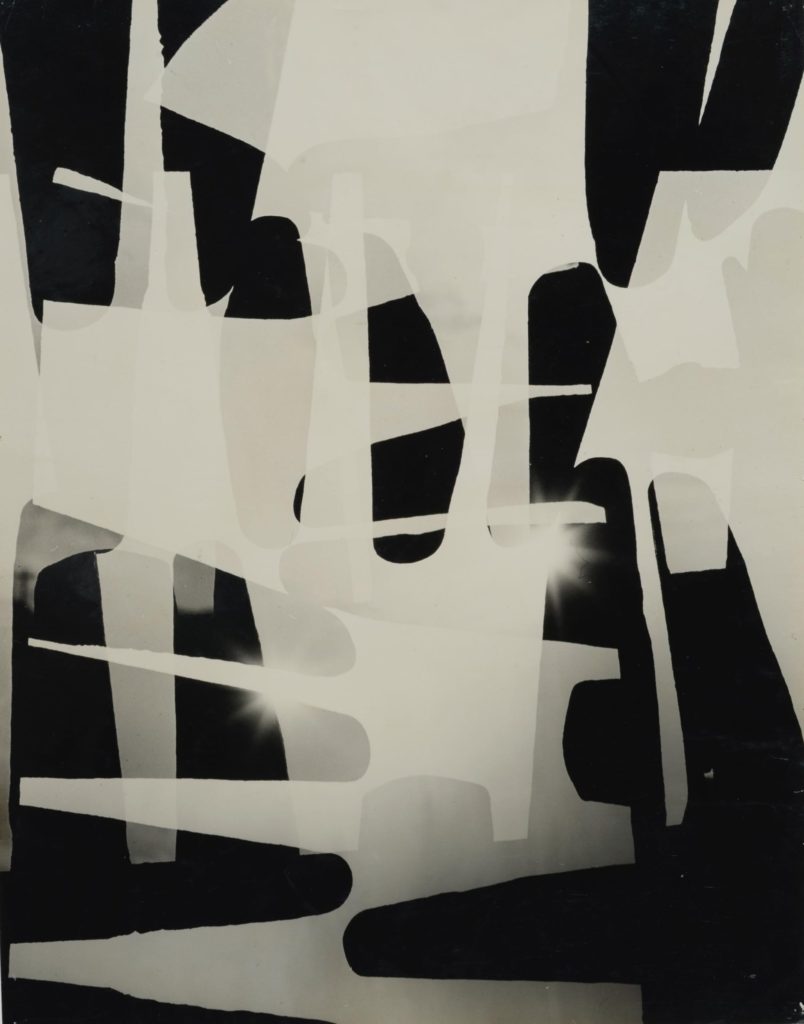

1956, Vintage gelatin silver print, signed on reverse of print, 42.4×33.1cm

1958, Vintage gelatin silver print, 44.7×56.3cm

1959, Vintage gelatin silver print, 42.9×34.6cm

1966, Vintage gelatin silver print, titled and dated on reverse of print, 28.6×43.3cm

Yoho Tsuda was born 1923 in in the village of Oto (now part of Gojo City) in Nara , to an affluent family that had been in the forestry business for generations. Following his father’s advice to serve his country as an engineer, he enrolled at the Yoshino Technical High School. He went on to join the Tokyo Industrial Arts High School (part of present-day Chiba University), but he quit after a while to enroll at the Nihon University’s College of Art as a film major. In 1943, he joined the navy as part of the conscription of students for World War II. A, he worked at his father’s company Tsuda Industries; when the company was later liquidated, Tsuda made up his mind to pursue photography.

After spending a year studying the basics of photography at the Osaka College of Photographic Arts, he began working for Shimada Shashinkan, a photography studio that specialized in portrait photography. At the time, there were five big photography clubs in Osaka: Tampei Photography Club, Naniwa Photography Club, Chiso-sha, Chikai-sha, and Daiken (the Osaka Photographic Research Society). Aspiring to become a fine art photographer, Tsuda became a member of the Naniwa Photography Club in 1949 on the recommendation of Atsushi Nakafuji, whose son happened to be a schoolfriend of Tsuda’s. Founded in 1904, the Naniwa Photography Club is Japan’s oldest organization of amateur photographers still active today. It has held regular exhibitions known as Nami-ten since the second year of its inception. The 1930s saw many proponents of the experimental Shinko Shashin (New Photography) movement emerge in close succession, and photographers such as Terushichi Hirai, Nakaji Yasui, Kiyoshi Koishi, Gingo Hanawa, Atsushi Nakafuji and Meison Kobayashi were establishing their names. However, Most of Osaka had been completely burned to the ground in the war, and at the time of Tsuda’s joining, the Naniwa Photography Club was holding its regular meetings in a cafe in a concrete building in Shinsaibashi-suji, one of the few left standing in the area. At his first regular meeting, Koro Honjo told him: “You and I are equals from this day on. There are no teachers here at Naniwa, so remember that and learn.”1 Naniwa Photography Club was known for its so-called “one-person, one-party” stance, which placed importance on its members’ individual expressions.

“The club’s interest originally lay in constructing forms. Patterns left by trickling paint, wormholes in wood, the shape of compressed metal – those were the sort of forms that we were pursuing. We were being held back by the influence of the pre-war days of Naniwa.”2 Tsuda’s works from this period were akin to so-called subjective photography, and revolved around their formal construction. At the time, the club’s members included photographers such as Gingo Hanawa, Atsushi Nakafuji, Terushichi Hirai and San’ya Nakamori, who had been members since before the war. These were joined after the war by Tsuda and Seizo Takada, then by younger photographers including Heihachiro Sakai, Yuzuru Nakafuji and Shosuke Sekioka. Thus it was that Tsuda’s generation gradually became the central figures of the Naniwa Photography Club in the post-war period.

It was around then that Tsuda saw the exhibition The Family of Man during its run in Japan,3 which left a profound impression on him. He was also inspired by the trend of social realism, championed by figures such as Ken Domon and Ihei Kimura, which was dominating the photography scene in Tokyo. Moving away from a style that was driven by formal or compositional concerns, he set out to produce photography that looked more closely at people’s lives. Partly induced by his academic background in cinema, he began to create narratives that consisted of a set of photographs with accompanying text. This was contrastive to the avant-grade photography scene in Kansai at the time, which held that the photograph itself should be the sole medium of expression, some going as far as to deem titles unnecessary.4

Tsuda left Osaka around 1955 and embarked on a journey to observe human lives, traveling along the Japan Sea coast in the Hokuriku and Tohoku regions. He would later compile these photographs in a series titled Nagisa (. Around 1959, he produced the series Kaiki (“Return”), a work that captured iron from its genesis to its dissolution, using it as a motif signifying reincarnation. Next came Shuen (“The End”), whose theme was dying beauty. This was also the period in which he produced Life in a Certain Mountain Village, a series about a village that was being swallowed up by a dam.

Tsuda’s visit in 1961 to the virgin forests of Odaigahara in Nara Prefecture sparked off a transition in his photography. His subject matter shifted from human lives to the trees and nature of Japan, and color photography slowly became his medium of choice. In 1977, he held an exhibition titled Ki to Hayashi (“Trees and Woods”) at the Fuji Photo Salon Osaka, which led to Poems of Trees, a solo exhibition three years later at New York’s Ronin Gallery. The Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired five of the exhibited works for its collection. In 1985, he held an exhibition titled Poems of Four Seasons and a Hundred Trees at the Daimaru Museum in Osaka, which then went on to other cities such as Nara (at the Nara City Museum of Photography), Tokyo and Yokohama. On the back of the exhibition’s success, he traveled around the whole country to produce a series on the theme of water titled Poems of Water, which was exhibited in 1988, touring nationwide. The final part of the trilogy that began with Poems of Four Seasons and a Hundred Trees and Poems of Water was Symphony “Poems of the ,” exhibited in 1994. Among the exhibits was a print of his photograph of the colossal Jomon Sugi tree on the island of Yakushima, which he had enlarged to its actual size, presenting an astonishing sight for visitors.

Tsuda took over from San’ya Nakamori as the head of the Naniwa Photography Club in 1998. In 2005, the club organized its centenary Nami-ten exhibition, which was held at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, the Irie Taikichi Memorial Museum of Photography Nara City, and the Keihan Gallery at the Keihan Department Store in Osaka. He passed away in 2014 at the age of 91, and the following year, the Yoho Photo Gallery was established in Shimanouchi, Osaka, to carry on introducing Tsuda’s work to the public. The gallery is also the of Naniwa Photography Club, and a place where the club exhibits the works of its members past and present.

Many of Yoho Tsuda’s photography series have been published, including Nagisa and the trilogy consisting of Poems of Four Seasons and a Hundred Trees, Poems of Water, and Symphony “Poems of the Earth.” Public collections that preserve his work include the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the planned (Nagisa), Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, Irie Taikichi Memorial Museum of Photography Nara City (Poems of Four Seasons and a Hundred Trees), Osaka Prefecture (Poems of Water) and the City Museum of Gojo Culture (Symphony “Poems of the Earth”).

__________________________________

1. Tsuda, Yoho. Ima wo Ikiru (“To Live Today”). p.83.

2. Ibid. p.83.

3. This exhibition was curated by Edward Steichen, then-director of the Department of Photography at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. It opened in 1995 at the same and went on to tour the world, including a run in Japan the following year at the Takashimaya Nihonbashi Store. It was a large-scale photography exhibition that aimed to capture through photographs the lives of the whole of humanity from birth to death, touring 35 countries and receiving more than 9 million visitors.

4. Ibid. p.86.