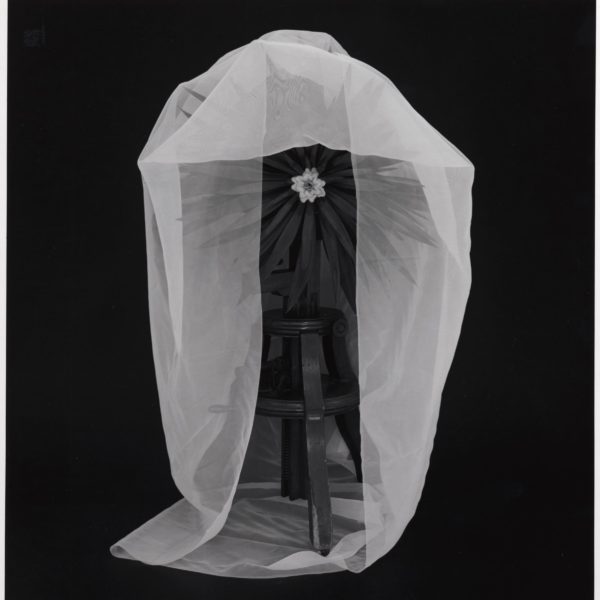

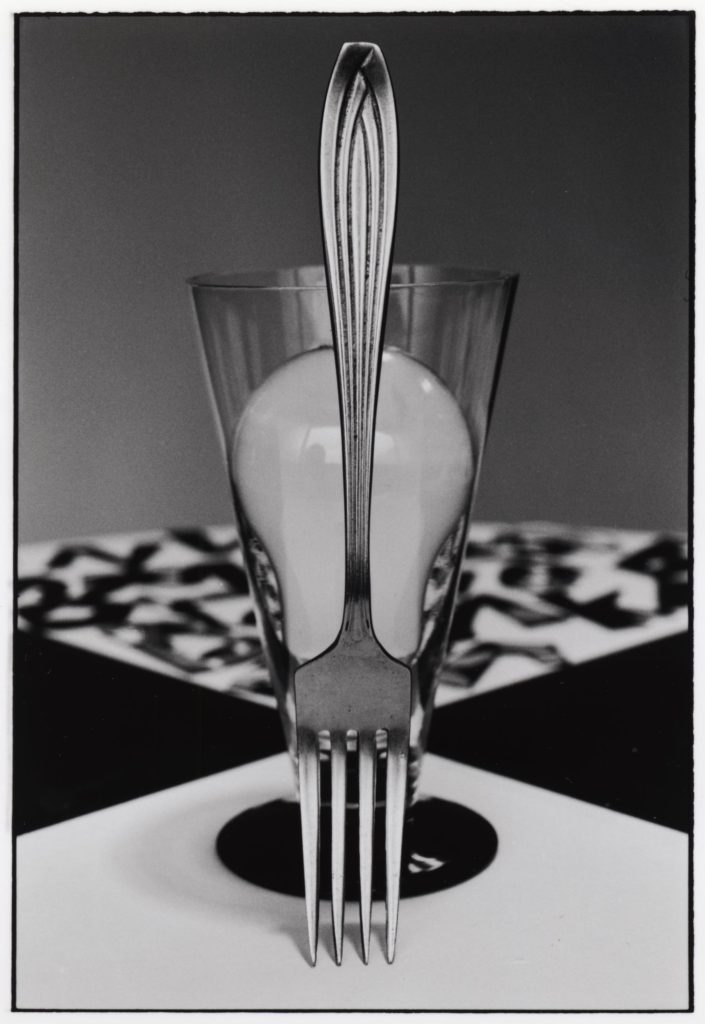

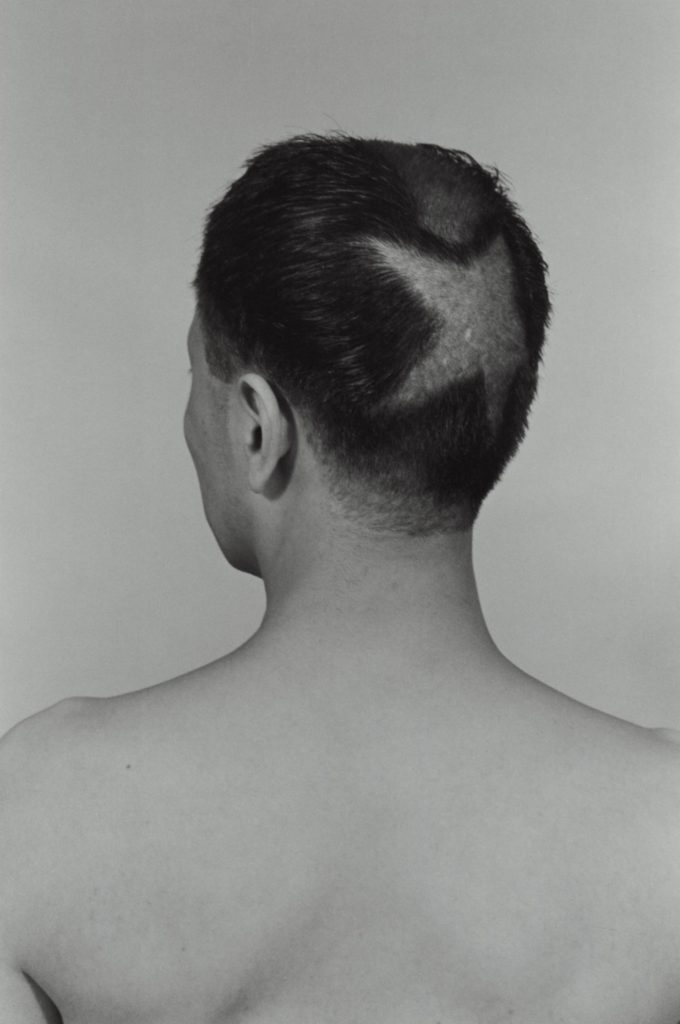

Gelatin silver print, 1984

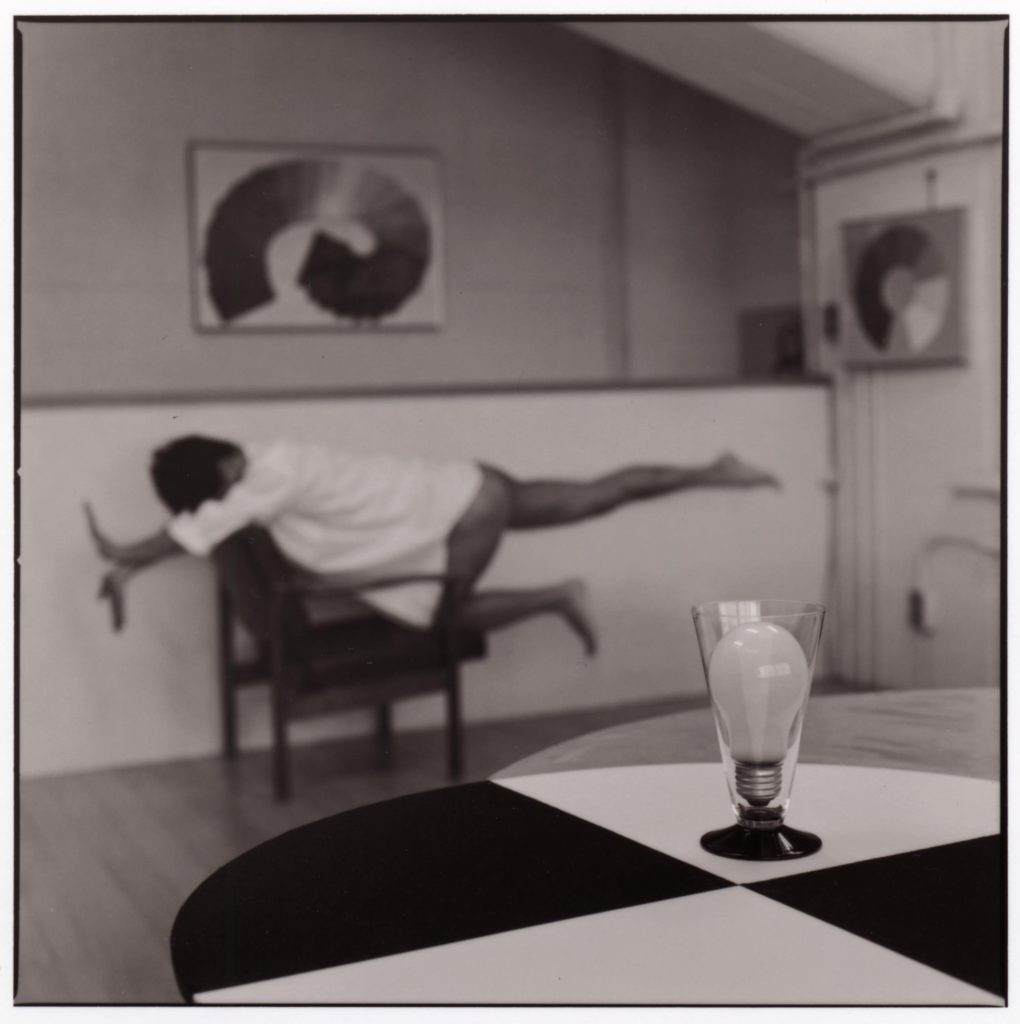

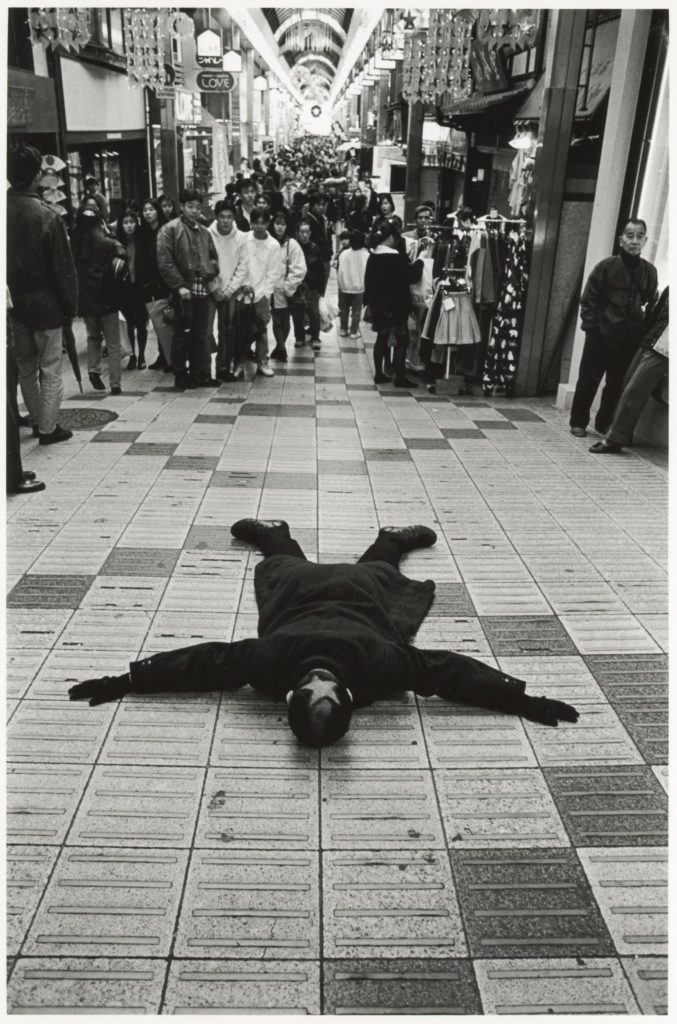

Gelatin silver print, 1984

Color photograph, 86.5×82cm, 1985

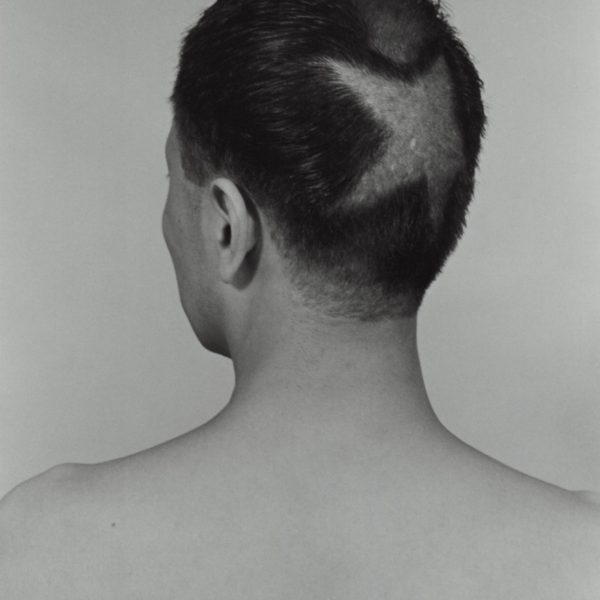

Gelatin silver print, 1990 / 2004

Gelatin silver print, 1990 / 2004

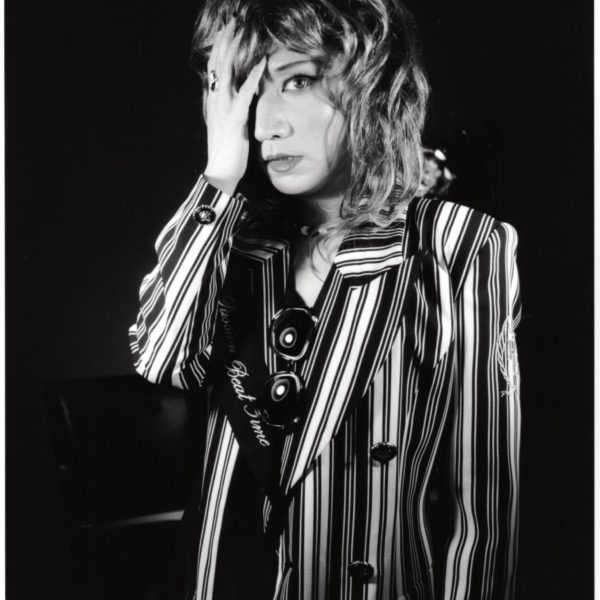

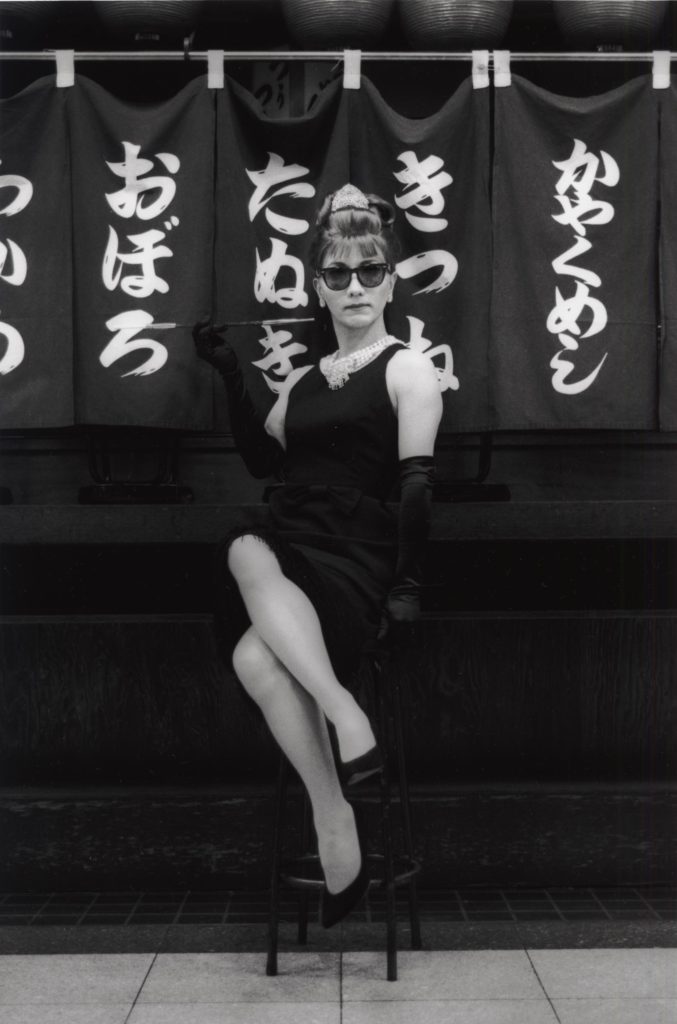

Gelatin silver print, 1995

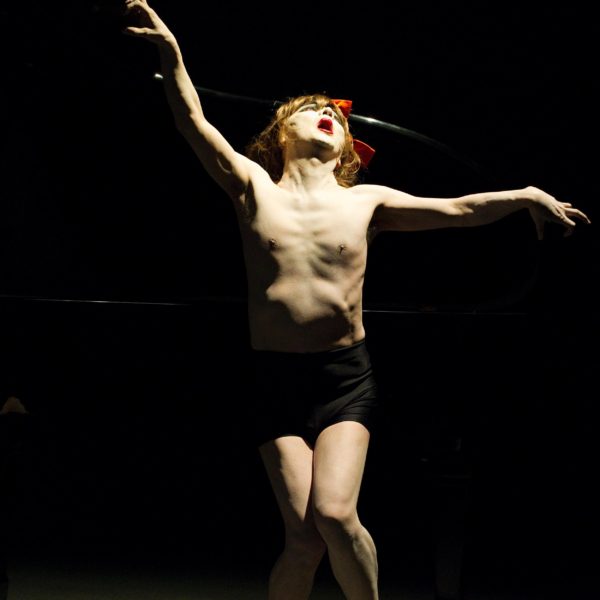

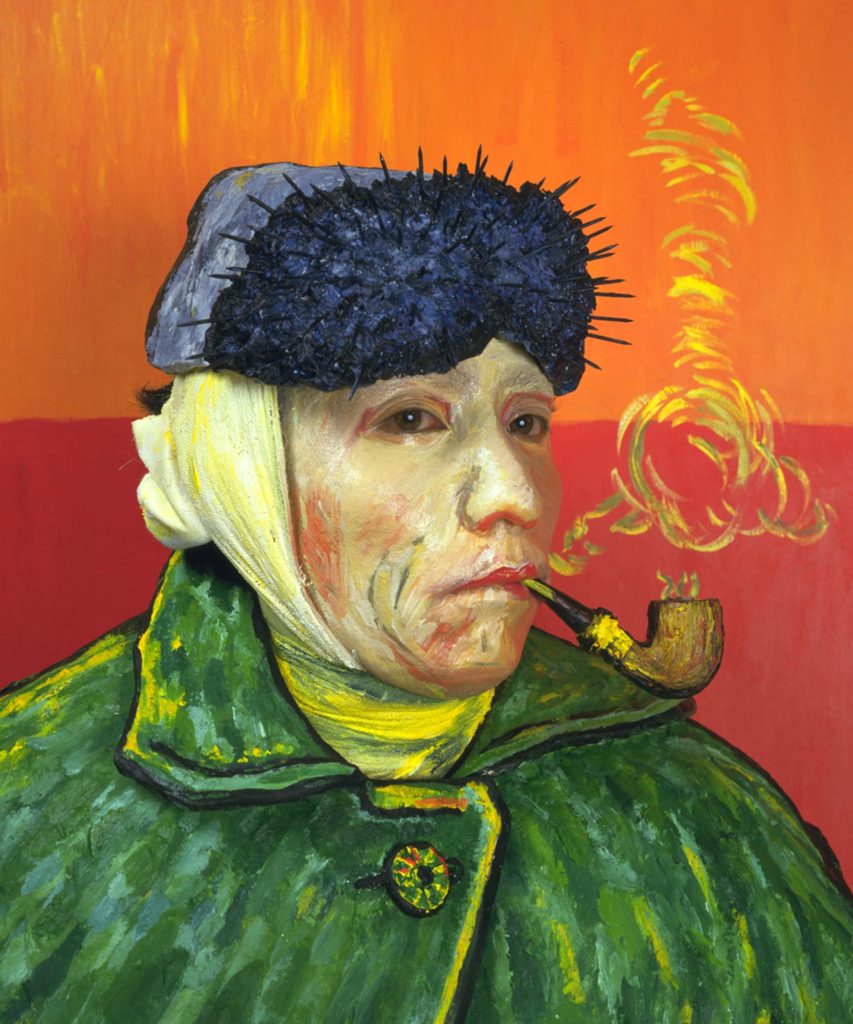

Color photograph, 2005

Gelatin silver print, 2018

Chromogenic print, 2010 / 2018

The Becoming Artist

Yasumasa Morimura is an artist who becomes someone (or something). Morimura transforms himself into people or things by freely inserting himself into famous paintings by masters of art history, including Van Gogh, Manet, Cézanne, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Goya, Leonardo, Rembrandt, Frida Kahlo, and Vermeer, and changing himself into Hollywood actresses such as Marilyn Monroe and Audrey Hepburn, and reenacting scenes from movies. While using his own body to enter Western paintings and episodes from the Silver Screen, Morimura is known for his use of devices that disrupt the binary schemes, such as Western and Eastern, female and male, and contemporary and ancient, in the original images. These include a version of Cranach’s Judith, which depicts a man in a topknot and a woman with a Japanese coiffure from the Edo Period, and a picture of Brigitte Bardot straddling a Harley Davidson in front of Osaka’s Tsutenkaku Tower.

While attending Kyoto City University of Arts, Morimura was deeply influenced by a class he took with the photographer Ernest Satow, a photojournalist known for his pictures in Life magazine and other publications. In addition to teaching photography, Satow taught his students about the Western modern aesthetic exemplified by the works of artists such as Henri Cartier-Bresson.1

After graduating, Morimura served as Satow’s assistant for a lengthy period. Then he made a series of photographic still lifes, all of which were shot indoors, called Barco negro na mesa. Using handmade props, and his own furniture and tableware, Morimura focused almost exclusively on the objects on the tabletop and in the room. However, the stable structure and composition of the works reflects the modern photographs and paintings that he studied in Satow’s class. The series also contained several of his first self-portraits.

In 1985, Morimura took part in a three-person show with Tomoaki Ishihara and Hiroshi Kimura called Smile with Radical Will, which was held at Galerie 16 in Kyoto. The exhibition included a self-portrait of Morimura disguised as Van Gogh in his famous self-portrait made after he had abruptly cut off part of his ear. At the time, the majority of Morimura’s works were conceptual and abstract, so the unusual nature of this piece attracted attention. While organizing a number of exhibitions with his friends from Kyoto City University of Arts, Morimura attempted to keep pace with the positive and bright fashion and art of the 1980s: “By striving to change my hairstyle, clothes, and aesthetic sensibility to fit the style of the ’80s, I acclimated myself to the era, but ultimately, I was really just a freeloader. My past efforts had been in vain, and although I was tossed around by the waves of the ’80s, it didn’t seem as if I would ever be able to generate the waves myself. When I realized that, I gradually started running out of breath, and could no longer move forward.”2 This experience inspired Morimura to confront the negative things that had prevented him from riding out the period, and to create a work based on the motif of Van Gogh, whom he saw as the epitome of negativity. This conversely had the effect of garnering Morimura a great deal of interest.

The Van Gogh self-portrait marked the start of Morimura’s Daughter of Art History series, which dealt with masterpieces of Western painting.

In 1998, Morimura was invited to show his work in the Aperto section of the Venice Biennale. This led to international acclaim, and a succession of foreign exhibitions. During that period, Morimura was often compared to Cindy Sherman, who portrayed various types of women in photographic series such as the famous Untitled Film Stills, which focused on scenes from B-movies. Although both Morimura and Sherman are “becoming” artists, Morimura uses his Japanese physique to intrude into the stage sets of renowned Western paintings. Inscribed beneath the humorous gestures are the confessions of an artist who wavers between Eastern and Western art. While in university, Morimura primarily studied Western art, and looking back on his education, he realized that both his knowledge and technique were part of the Western tradition. From the time that Morimura was a child, the most famous artists were people like Van Gogh and Picasso. Consequently, it was natural for him to approach art from the perspective of Western history. But Morimura has said that he does not consider the sensibility that was formed under these circumstances to be either healthy or balanced.3

The Self-Portraits of YASUMASA MORIMURA: My Art, My Story, My Art History, an exhibition held at the National Museum of Art, Osaka in 2016, consisted of both old and new works, including a comprehensive series dealing with Western and Japanese art history as well as a full-length film, which paid homage to various artists from the Renaissance to the contemporary era. Morimura also showed a number of works that reexamined modern Western-style painters such as Shigeru Aoki, Tetsugoro Yorozu, and Shunsuke Matsumoto. Like Morimura, these pioneering artists searched for their own unique forms of expressions throughout their lives while confronting Western art.

Along with performances and stage activities, Morimura has from the outset made related video works. His first video work, Cometman (1990), documents a performance in which, after shaving a star into his hair (in the manner of Marcel Duchamp in Man Ray’s famous portrait), Morimura walked around the city of Kyoto. Other video works that document the artist’s performances include Three Films for Kazuo Ohno’s La Argentina and High, Red, Central, Action.

Morimura has also presented public performances, taken part in stage productions, and appeared in movies. These include collaborations with the butoh dance company Dairakudakan (1994, 1995); a performance with Masami Tada called Technotherapy / Special Night (1998), part of a comprehensive art event called Technotherapy (Osaka City Central Public Hall), for which Morimura also served as director; a stage production directed by Yukio Ninagawa called Pandora’s Bell (1999), in which Morimura played Mrs. Pinkerton; and Jinsei Tsuji’s film Filament (2002), in which Morimura played the owner of a photo studio with a penchant for cross dressing. More recently, Morimura created a link between his own family history, Japanese war history, and art history in Nippon Cha Cha Cha!, a stage production in which he discussed the special circumstances of Japanese culture as viewed through the lens of his works. The piece was presented in 2018 at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, Theater Commons in Yokohama, and the Japan Society in New York.

At MEM, Morimura first introduced a series of still-life photographs, which served as a compilation of his pre-Van Gogh portrait works in Barco negro na mesa (2003). Two years later Morimura presented Vermeer’s Room (2005), a reproduction in the gallery of the room depicted in Johannes Vermeer’s work The Art of Painting. After MEM moved to Tokyo, Morimura showed The Genesis of “I” (2016), an exhibition of his early works, including Cometman, the work based on the Duchamp portrait, and High Red, Central, Action (2018), a work focusing on Hi-Red Center, one of the most important postwar Japanese avant-garde art groups. While considering Morimura’s use of his body throughout his career, as seen in his art history series and other works, this exhibition introduces a wide range of the artist’s activities, including his photographs, performances, and videos.

(K.I.)

____________

Notes

1. Yasumasa Morimura, An Anatomy Lecture in Art, Heibonsha, p.50.

2. Yasumasa Morimura, The Making of Artist M, Chikuma Shobo, p.45.

3. Yasumasa Morimura, “About My Work,” Daughter of Art History: Photographs by Yasumasa Morimura, Aperture, 2005.