MEM presents Vermeer’s Room, an exhibition of installation work by Yasumasa Morimura, which pays an homage to Johannes Vermeer, the Dutch master in the 17th century. The whole project began with a painting titled The Art of Painting by Vermeer, which was exhibited last year in Japan as part of collection of Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Morimura recreated the actual room in the original painting including furniture and props in his own manner. He used computer analysis to verify the exact dimension of the room, locations of props and sizes of persons. He eventually produced a piece of canvas work based on The Art of Painting by Vermeer imposing himself as the painter and the model at the same time.

Related photographs and a video work will be shown in the exhibition. In Vermeer’s Room, you can experience an imaginary Vermeer’s room created by Morimura.

Press

Courtesy Art Asia Pacific magazine

Exclusive

Out of the Corner of a Small Room, Painting Develops

In a new installation piece displayed at MEM, Osaka, in July 2005, Morimura Yasumasa recreated in three-dimensional exactitude the room depicted in Johannes Vermeer’s masterwork, The Art of Painting (c. 1662-68). Based, however, not on the concept of architectural mimicry or deference to one’s forbears, but instead on the wish to welcome guests into his own satellite atelier, Morimura explains the work as being informed by Vermeer, yet centered on the Japanese tradition of shitsurae, or the careful placement of objects in an intimate setting so as to enhance the experience of one’s guests engaged in a formal tea ceremony. Under such a scenario, the meticulously arranged ikebana floral displays, revered tea implements, sweeping garden views and laboriously chosen hanging scroll of the teahouse are replaced with the trappings of The Art of Painting, yet served up with Morimura’s signature twist. Laden with hidden meanings and veiled references, Vermeer’s Room (2005) can best be viewed as an iconographic study of the fine art of trickery and well-intentioned deceit.

At first glance, the installation’s layout appears to be a perfect replica of Vermeer’s studio where so many of his paintings were composed: pure light seeps in from the window to the left; the signature black and white checkered floor draws the eye; the heavy wooden furniture is placed exactly where it should be. Yet, upon closer inspection, the entire scene starts to unravel as Morimura’s playful stunts become apparent. The spatial arrangement of the room and the abundance of photographs of the same interior that line the wall allow for the piece to exist on a number of planes, some physical, others philosophical. These attendant portraits and a framed video work that sits on a chair just in front of the large table in the room are at times populated by various incarnations of Morimura playing the two key roles in the original painting: Vermeer himself, and a model portraying Clio, the muse of history. Many of the photographic works depicting the room, however, are devoid of Morimura, thus leading the viewer to wonder what further tricks he may be concocting offstage. And we do see the constructed nature of these tricks in the key to the series, Vermeer: The Positions of the Three (2004), a behind-the-scenes view of the set for Vermeer Study featuring Morimura facing the camera in Vermeer’s clothing and standing in the same position as the camera obscura that Vermeer used to spatially arrange the layout of the original painting.

The clues to the work’s visual puns are hidden in the tomes of art history, and it is only with a careful iconographic study of the original Vermeer that one begins to understand Morimura’s master plan. For, itself rich in iconographic reference, The Art of Painting is first and foremost an allegorical tale about fame, power, patronage and painting that was conceived of in a 17th-century Netherlands fully entranced by all of these things and more. For example, Vermeer depicts Clio wearing a wreath of laurel on her head and holding a trumpet and a thick portfolio, one in either hand. The trumpet is a sign of fame; the book a reference to arts and letters; the combination, a reference to the fame bestowed on an artist thanks to literary acumen or aesthetic skill. So, too, is the black and white marble floor a nod to the wealth of the era, although it is quite likely that Vermeer’s studio did not have such a floor, and that the artist was simply intrigued by the pattern as an artistic challenge or a reference to the wealthy arts patrons whom he was hoping to attract. The large map hanging on the back wall of the room depicts the 17 unified districts of Holland under former Hapsburg rule; the Latin phrase at the top makes timely reference to warfare and political power. Lastly, the scattered drawings and plaster cast of a head atop the table make reference not only to the value of study models in painting, but also to the import of history and the celebration of its heroes through the, then, vogue display of death masks, bust portraiture and graphic representations of the important politicians and philosophers of world history.

Vermeer’s careful iconography is mirrored askew in Morimura’s work and is best viewed in the main focal point of the installation, the large portrait Vermeer Study: A Great Story Out of the Corner of a Small Room (2004), that hangs on the back wall of the installation. The replacement of the map from The Art of Painting with this photograph can thus be seen as a device to place artistic prowess on the same level as military might and political power. Within this work, and amongst the real-life arrangement of its props and remains scattered around the room, Morimura carefully references Vermeer’s iconographic lexicon, while at the same time establishing his own. Here, for example, we still find Clio bedecked with a (fresh) laurel wreath and holding an (actual) brass trumpet and a thick historical atlas, but in Morimura’s world, the role is not played by a model, but by the artist himself, carefully “made up” in all aspects of the word to resemble the Clio of the original. The artist at the easel, too, is played by Morimura, this time in the role of Vermeer himself; the work thus becomes a multilayered self-portrait of the artist painting a portrait of his own, albeit in drag, self-portrait.

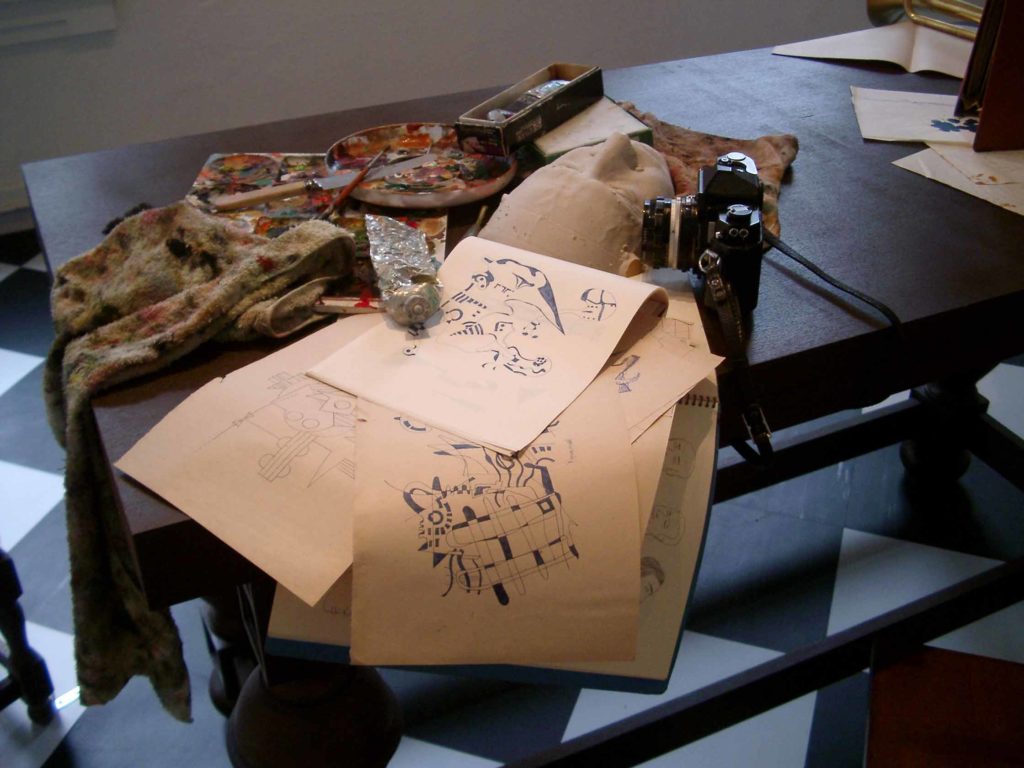

The placement of well-planned puns does not end with Clio, however. In Vermeer’s Room, the various objects that inhabited the top of the table in Vermeer’s work are replaced by items significant to the history of Morimura’s career as an artist. The plaster bust is there but is, in fact, a cast of Morimura’s visage and perhaps a conscious act of forced inclusion into the annals of art history. The drawings and sketches that cover the top of Morimura’s table are works that he drafted as a high school student and can thus be read as precursor hints that shed light on the development of his work. In addition to the tattered rags and tubes of paint—incredibly important tools of the art trade—that litter the table, there is also to be found the most indispensable tool of Morimura’s art making: his beloved camera. It is here that his most profound trickery—that of placing the value of photography over that of painting—is performed.

And so it is through the lens of Morimura’s camera that Vermeer Study is produced, a photograph in painting’s clothing. Thought of in these terms—“dressing” a room so as to replicate a given space (or architectural drag, if you will)—Morimura’s attention to detail is seen not only in the folds and drapes of the figures’ clothing, but also in the hand-painted curtain that hangs before much of the upper-left quadrant of the work. It is upon this curtain that Morimura’s “art of painting” plays out in his attempts to mimic the fine tapestries depicted in The Art of Painting’s drapes. So, too, does it play out in the laurel wreath depicted on the canvas left behind in the installation, a balancing rod looming upon its surface as if levitating. But perhaps most important to the overall understanding of all of the works is the painted map that hangs at the back of the small room in Vermeer Study.

Surprisingly not a depiction of the 17 districts of Holland, Morimura’s map is instead that of the world. Its roughly etched lines mimic that of the map in the Vermeer, and along the bottom, small flags of each nation of the world are illustrated. A female figure in the upper right corner holds the coats of arms of the north and south regions of the Netherlands, one in each hand; she is the emblem of “unity and separation,” just as she is in the Vermeer, although here her role is that of the mediator between photography and painting, not North and South. Returning to the Latin heading of the map in The Art of Painting, the text reads (in translation): “The tremendous wars waged in these countries in bygone days, and still waged in these days, bear sufficient witness to the whole wide world of the great strength, power, and wealth of these very countries.” Turning to the text on Morimura’s map, a very different message—this time in Dutch—is to be found. It says (in translation): “A Great Story Out of the Corner of a Small Room.” And it is indeed from the installation’s very small room—along with its trappings and the photographic and video depictions that simultaneously interpret and inhabit it—that a most interesting story revolving around artistic fame, power, politics and painting develops, much akin to the same story spun by Vermeer nearly 400 years ago, and more directly, in the same vein as Morimura’s photographic output.

– Eric C. Shiner

On Mono, Koto and Body – Six Perspectives

On Mono, Koto and Body – Six Perspectives  Yasumasa Morimura “High, Red, Central, Action”

Yasumasa Morimura “High, Red, Central, Action”